China’s battle against inequality

China’s central government is flexing its muscles in a determined effort to ensure that Chinese society is shaped in keeping with the leadership’s communist philosophy. The most important recent developments are:

- The regulatory framework is being tightened, especially with regard to business activities that are thought to endanger the wellbeing of the young.

- The exploitation of user data by private companies is being regulated. The targets are online platform providers like Alibaba that have acquired a virtual monopoly in the market. Dubious practices are being banned.

- Action is being taken to mitigate the rising cost of living for low-income families. The real estate market is seen as a major driver of price increases.

- The Chinese leadership’s long-standing opposition to foreign stock exchange listings for Chinese companies is being stepped up, as the vehicle hire company DiDi discovered to its cost when it went public on the New York Stock Exchange. At the same time, the US Securities and Exchange Commission has warned against business structures known as variable interest entities (VIEs) that are used by Chinese companies to skirt restrictions on foreign listings.

- Despite a high vaccination rate – 76% of the population had received at least one jab by the start of September – China is sticking to its “zero Covid” strategy. Strict local lockdowns are denting economic recovery. Leading indicators have recently been in retreat.

What does the Chinese government want to achieve?

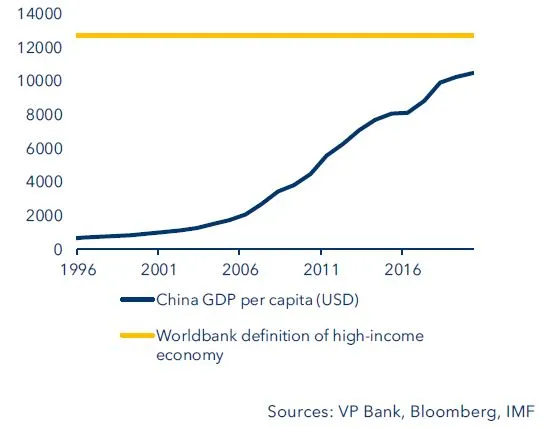

At first sight these measures may look arbitrary and haphazard, but they should be seen as part of a course correction designed to ensure continuing economic progress. China’s economic advance has been an unprecedented success story. The groundwork was laid by the reformer Deng Xiaoping, who took office in 1978. In that year 98% of China’s population lived in poverty. Forty years later, according to the National Bureau of Statistics, this figure had dropped to 3%. Per capita income in China has climbed over tenfold since the country’s admission to the World Trade Organisation just under twenty years ago. The IMF now expects per capita income to rise to USD 11,819 p.a. by the end of this year, putting China on the verge of qualifying as a “high income economy”. This is a crucial step that has eluded many emerging economies in the past (cf. our investment magazine Telescope no. 3, “Emerging markets reappraised”.

Chinas economic rise

The prioritisation of economic growth has pushed many other policy concerns onto the side lines. The Communist Party’s approach has been pragmatic, as summed up by Deng Xiaoping’s famous remark: "Black cat or white cat, if it can catch mice it's a good cat." The biggest challenges created by China’s often unbridled capitalist model are:

- corruption

- environmental pollution

- unequal distribution of income and wealth

As soon as he took office, President Xi Jinping declared war on rampaging corruption. World Bank data show that the crackdown has achieved results. The corruption index for the public sector is now lower than at any time since the early 1980s. Many Communist Party members have fallen foul of the anti-corruption drive. Xi’s tough approach enjoys wide support among the population at large, which has also warmed to his nationalist rhetoric.

Similar success has been achieved in the battle against atmospheric pollution. According to measurements by the US embassy in Beijing, the concentration of fine particulate matter in the capital’s atmosphere is now 60% lower than in 2013, the year when Xi became President. The authorities have certainly not pussy-footed. Almost 2,000 businesses in Beijing have been closed down (cement works, foundries, coal-fired power stations) and two million vehicles have been taken off the road.

The third problem – economic inequality – remains unresolved. From the late 1970s onwards, it was accepted that some citizens would become rich much faster than others. Incomes and wealth are now hugely unequal. These disparities jeopardise social stability and economic progress and ultimately pose a threat to the Party’s grip on power.

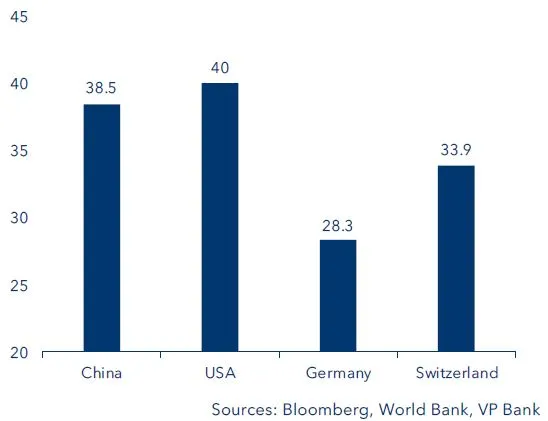

China’s economic growth has brought a widespread improvement in prosperity, but the benefits have been spread very unevenly. According to the World Bank, China’s “Gini coefficient”, which measures income inequality across the population, now stand at 38.5, which puts it closer to the US than to Germany (the lower the figure, the smaller are the inequalities in income). No other country has more billionaires than China. At the same time, a lack of prospects is causing more and more well-educated young city dwellers to renounce the work ethic and opt for a drop-out lifestyle.

Income distribution (Gini coefficient as %)

The government’s latest actions suggest that it intends to pursue the aim of a fairer distribution of income and wealth with the same rigour as it showed in the battles against corruption and atmospheric pollution. Recent measures are intended to help low and middle income earners by targeting activities that put an excessive strain on their finances. Thus, the private education sector, notably after-school cramming, has been massively downsized in order to relieve the financial burden on parents. This also increases the incentive to have a second or third child, a trend that would help counter the problem of China’s aging population. In another move, the government has decreed that young Chinese are no longer allowed to devote more than three hours a week to online gaming. This measure has obvious implications for the tech giant Tencent as well as foreign gaming providers. Tougher regulations are likewise to be imposed on traditional gambling. The government is also targeting tech companies and online platform providers that exploit their huge databases and algorithms to fix user-specific prices and steer customers’ buy decisions.

The market power that tech companies have amassed thanks to their mammoth stores of user data is also viewed critically by governments in the US and Europe. But the Chinese authorities, unlike their western counterparts, have no qualms about intervening in market competition. The top priority is the public good rather than private wealth or the health of individual companies.

Alongside these measures, China could also use tax changes to achieve a fairer spread of incomes. The effective average rate of income tax, at 7%, is much lower than in most other countries, and taxes on capital gains or inheritance are unknown. New and/or higher taxes would therefore make sense. The introduction of a real estate tax, for example, has repeatedly been postponed, but could well be put on the agenda again.

Implications for the financial markets

China is still committed to economic expansion, but the emphasis of economic policy is shifting. For the first time ever, the current five-year plan (until 2025) contains no numerical growth targets. This is a strong indication that qualitative growth will now take centre stage.

The new “common prosperity” push is intended to achieve a fairer distribution of affluence, enabling more citizens to share in the proceeds of economic progress. But China’s leadership does not intend to resort to Robin Hood methods. The rich are not going to be robbed to help the poor.

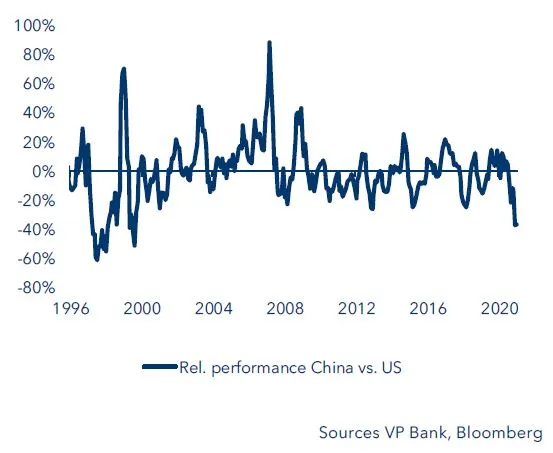

These policies are basically positive for China’s long-term growth outlook. Yields on Chinese government bonds have hardly changed at all in recent months. But the impact on individual firms varies. Heavier government intervention, increased regulation and potentially higher taxes are intrinsically negative for corporate earnings. This applies primarily to tech companies, platform providers, real estate companies and the energy sector. Businesses in the consumer sector, by contrast, stand to benefit from improved purchasing power in the population at large. Providers of sustainability solutions should also be among the winners. The Chinese equity markets’ negative reaction to the recent measures is partly due to the fact that the market is now dominated by tech companies, as in the US. Moreover, many international investors have reacted by pulling out of China for the time being and switching to the US market. Chinese equities’ underperformance vis-à-vis the US has reached historic proportions.

Relative performance of Chinese equities vs US

In the bond market, the heaviest pressure has been felt in the highly leveraged real estate sector. The government wants to skim the froth off the over-heated real estate market and is now less ready to bail out companies in trouble.

How should investors respond?

We still regard Chinese government bonds, “policy bank” bonds and high-quality corporate bonds as an attractive supplementary component of investment portfolios. The risks surrounding economic growth are being addressed by the government’s actions, and these investments should also continue to benefit from investors’ increased need for security.

We recommend a differentiated approach to Chinese equities. Important political landmarks are approaching – a plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party in November and the 20th Party Congress in March at which Xi will apply for re-election. In the meantime, further regulatory measures could be on the cards. Firms that the “common prosperity” policy does not affect (or affects only marginally) have come under much less pressure and should benefit from the change of course. For an appropriate product recommendation, please contact your customer advisor.

|

Download |

Important legal information

This document was produced by VP Bank AG (hereinafter: the Bank) and distributed by the companies of VP Bank Group. This document does not constitute an offer or an invitation to buy or sell financial instruments. The recommendations, assessments and statements it contains represent the personal opinions of the VP Bank AG analyst concerned as at the publication date stated in the document and may be changed at any time without advance notice. This document is based on information derived from sources that are believed to be reliable. Although the utmost care has been taken in producing this document and the assessments it contains, no warranty or guarantee can be given that its contents are entirely accurate and complete. In particular, the information in this document may not include all relevant information regarding the financial instruments referred to herein or their issuers.

Additional important information on the risks associated with the financial instruments described in this document, on the characteristics of VP Bank Group, on the treatment of conflicts of interest in connection with these financial instruments and on the distribution of this document can be found at https://www.vpbank.com/legal_notes_en.pdf